“As he took the lead what a roar of excitement went up! Tens of thousands of dollars were in suspense, and although I had not a cent depending, I lost my breath, and felt as if a sword had passed through me.” — Josiah Quincy, Jr.

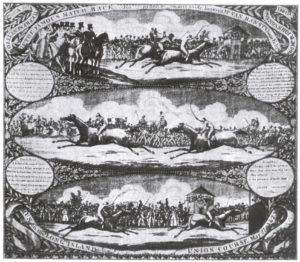

The Great Match Race: The First Heat

The moment had finally arrived for the commencement of the Great Race – if only the course was clear! The track itself was thronged with spectators for a quarter mile in each direction from the judges’ box, and it was no simple task to remove the legions of fans. It took the arrival of the two magnificent beasts onto the course to empty the area.

“They were both in brave spirits, throwing their heels high into the air,” recounted Josiah Quincy, Jr., about American Eclipse and Sir Henry; “they soon effected that scattering of the multitude which all other methods had failed to accomplish.”

Lots were drawn and Eclipse was given the inside post; his jockey, a young man named William Crafts, wore the crimson color of his horse’s owner, C.W. Van Ranst. Sir Henry was appointed to stand twenty-five feet away to the outside, and his rider, John Walden from Virginia, wore Colonel Johnson’s sky blue colors on his jacket and cap.

With the tap of a drum as the signal to start the first four-mile heat, the pair was off and running, Sir Henry accelerating to take the lead. He maintained it at a lightning-fast pace by about three lengths, mile after mile, until reaching the far turn of the fourth and final mile.

In the stretch, Crafts asked Eclipse under profound use of the whip, while Walden continued Henry’s dominating run without any urging.

“I clearly saw that Crafts was making every exertion with both spur and whip to get Eclipse forward, and scored him sorely, both before and behind the girths,” reported Cadwallader Colden, a.k.a., “An Old Turfman,” who followed the action of the race while on horseback.

“At this moment Eclipse threw his tail into the air, and flirted it up and down, after the manner of a tired horse, or one in distress and great pain; John Buckley, the jockey, (and present trainer) who I kept stationed by my side, observed ‘Eclipse is done.’”

Billy Crafts, a slight young man of 100 lbs., was incapable of commanding the great Eclipse with one hand, while he continued covering him with blows with his whip in the other.

“Buckley exclaimed (and he well might), ‘Good G-d, look at Billy,” Colden recounted. The boy had flung his body far back in his wobbling saddle, attempting to support himself by sticking his legs straight forward in the stirrups, which only further taxed the champion in the final quarter.

Under Crafts’ heavy hand, Eclipse had made up two-thirds of the distance between himself and his challenger. Yet Henry prevailed, coming home about a length ahead in record-breaking victory – time, 7 minutes, 37½ seconds, according to the judges (and 7:40 based on the watches of several in attendance). The time of this heat shattered Sir Hal’s four-mile record of 7:42, set in 1814 at Broad Rock, Virginia.

Colden promptly arrived at the finish line to assess the state of the two beleaguered horses. While Sir Henry appeared to be less weary than anticipated, Eclipse’s suffering was obvious: “Crafts in using his whip wildly, had struck him too far back, and had cut him not only upon his sheath, but had made a deep incision upon his testicles, and it was no doubt the violent pain occasioned thereby, that caused the noble animal to complain, and motion with his tail, indicative of the torture he suffered.”

“The blood flowed profusely from one or both of these foul cuts,” Colden continued, “and trickling down the inside of his hind legs, appearing conspicuously upon the white hind foot, and gave a more doleful appearance to the discouraging scene of a lost heat.”

New York and its supporters were aghast, while the Southern spectators cheered with thunderous applause for their triumphant hero.

“The result of this heat was so different from what the northern sportsmen had calculated upon, that the mercury fell instantly below the freezing point,” said the New York Evening Post. “Bets three to one that Eclipse would lose the second heat were loudly offered, but there were few or no takers.”

The Second Heat

A rider change for the second heat was imperative. Racing folklore, however, tells conflicting accounts of how American Eclipse’s rider, Samuel Purdy, was secured.

Purdy, a retired former rider for the champion, had come prepared to the Union wearing the crimson colors of Van Ranst under a large coat. Although he’d previously fallen out with the owner, Purdy approached Van Ranst in tears following the loss of the infalliable horse in the first heat, imploring him to be allowed to ride.

Members of the Northern syndicate, it has otherwise been told, did the pleading with Purdy to take over the mount. The 38-year-old man initially balked at the offer – feeling that he wasn’t in shape to ride – but he finally agreed.

With Purdy enlisted as Eclipse’s pilot, the horses were led back to the start, Sir Henry taking the inside of the track. The break of 30 minutes from the previous heat had invigorated the North’s gallant steed, according to Colden: “I attentively viewed Eclipse while saddling, and was surprised to find that to appearance he had not only entirely recovered, but seemed full of mettle, lashing and reaching out with his hind feet, anxious and impatient to renew the contest.”

With another tap of the drum the rivals took flight, Sir Henry again securing the lead and maintaining it by two lengths until the third mile. Purdy launched his run at the leader in the home stretch, and by the wire Eclipse had gained significant ground to reach the heels of his adversary.

The cheers of the crowd were overcome by the piercing screams of the Honorable John Randolph of Roanoke – the Virginia statesman and master orator, close friend of the absent Napoleon of the Turf, and horse breeder and authority on pedigree in America and abroad. Josiah Quincy, Jr., who was sitting directly behind Randolph, remarked:

At every spurt [Eclipse] made to get ahead, Randolph’s high-pitched and penetrating voice was heard each time shriller than before:

You can’t do it, Mr. Purdy!

You can’t do it, Mr. Purdy!

You can’t do it, Mr. Purdy!

As the horses rounded the turn for the final mile, Eclipse continued his chase, gradually advancing on Sir Henry. The two were neck and neck in the back stretch, and by the time the duo rounded the far turn, Purdy had done it – he had passed the North Carolina chestnut, and was soon clear by a head.

“As he took the lead what a roar of excitement went up!” Quincy exclaimed. “Tens of thousands of dollars were in suspense, and although I had not a cent depending, I lost my breath, and felt as if a sword had passed through me.”

Eclipse sustained the lead as they headed for home, and steadily drew away from Henry. Colden recounted:

As they passed up the stretch or last quarter of a mile, the shouting, clapping of hands, waiving of handkerchiefs, long and loud applause sent forth by the Eclipse party, exceeded all description. It seemed to roll along the track as the horses advanced, resembling the loud and reiterated shout of contending armies.

The nine-year-old horse crossed the finish line two lengths ahead of young Henry, in a time of 7 minutes 49 seconds. Members of the throng swarmed the winner, and hoisting the jockey into the air, they carried him upon their shoulders around the track in jubilant celebration amidst the shouts of “Purdy Forever!”

The mighty Eclipse had been redeemed, and “the mercury in the sporting thermometer immediately rose again to pleasant summer heat,” wrote the Post.

Northerners offered to bet even on the third heat, while some Sir Henry supporters proposed to end the match as a draw, with no takers from either side. For this last race, it was the Southerners who made a jockey change – John Randolph of Roanoke having persuaded Johnson’s trainer Arthur Taylor to ride Sir Henry for the final heat.

The Final Heat!

The competitors were led back to the starting line, and Eclipse was positioned on the inside. At the signal, the horses were off, Eclipse on the lead this time and keeping it for each of the four miles, Henry following two lengths behind.

When the horses neared the final furlong, the colt began to quicken. He made up enough ground to reach the old horse’s haunches with his nose, straining to remain in contention with his rival. Despite his valiant surge, however, Henry could not pass the old horse, nor continue to keep pace with him.

As Eclipse crossed the finish line three lengths ahead in a final time of 8 minutes 24 seconds, “a shout went up that seemed to rend the heavens,” reported the Catskill Recorder.

Tens of thousands of men mobbed the course. After much time and maneuvering, the horses managed to move through the crowd and arrived at the judges’ stand to be weighed, and Eclipse was officially pronounced the winner.

The nine-year-old champion, still proven invincible, was then led from the track to a band’s resounding rendition of “See, the Conqu’ring Hero Comes:”

See, the conqu’ring hero comes!

Sound the trumpets, beat the drums.

Sports prepare, the laurel bring.

Songs of triumph to him sing.See, the godlike youth advance!

Breathe the flutes and lead the dance.

Myrtle wreaths and roses twine,

To deck the hero’s brow divine.See, the conqu’ring hero comes!

Sound the trumpets, beat the drums.

Sports prepare, the laurel bring,

Songs of triumph to him sing.

Despite his loss, Sir Henry was held in high esteem for his fortitude. Colden remarked about the impact of the weight factor on the younger horse’s performance in the third heat, during which he carried 110 lbs. – an extra two pounds over the weight for four-year-olds. “It not being possible to bring Arthur Taylor to ride less, and although a small horse, and wanting twenty days of being four years old, he made the greatest run ever witnessed in America,” said the Old Turfman.

The Northern syndicate, and members of the New York Association for the Improvement of the Breed of Horses – the club that managed the Union Course – closed the day with a festive dinner at the track’s pavilion, during which several toasts were made:

By the Association President, Judge Van Ness: “Eclipse – still the best courser of his day.”

By R. Emmet: “Henry – the best four-year-old horse in the country.”

By General Barnum: “Our opponents of the South – Gentlemen in prosperity and in adversity.”

By Samuel Purdy: “Eclipse! Too fast for the speedy and too strong for the stout.”

By John C. Stevens: “The better health of Wm. R. Johnson, the trainer of a four-year-old to run a four-mile heat in 7:40.”

Up Next: Part IV. — The Aftermath!

Missed the preceding parts of this series? Catch up on Part I., Napoleon Challenges the North, and Part II., Which Hero of Napoleon’s Southern Army Will Face Eclipse? here!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.