“On arriving, we found an assembly which was simply overpowering; it was estimated that there were over one hundred thousand persons upon the ground.” — Josiah Quincy, Jr.

Colonel Johnson rallied the resources of the South in the months leading up to the four-mile match, and put into training an army of five exceptional horses to determine American Eclipse’s most redoubtable opponent.

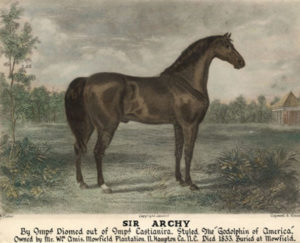

Each was the progeny of Sir Archy, the “Godolphin Arabian of America” and champion four-miler previously trained by Johnson:

- Six-year-old Flying Childers from Virginia, out of the Robin Mare, by Robin Redbreast;

- John and Betsey Richards, four and five-year-old brother and sister from Virginia and South Carolina, respectively, dam by Rattle, son of Shark;

- From the North Carolina stable of Johnson’s father Marmaduke, a grandson of Sir Archy, four-year-old Washington, by Timoleon, out of Ariadne by Citizen; and

- The four-year-old Sir Henry, out of a mare by Diomed, also from North Carolina. As a June foal, Sir Henry was the youngest of the five and still in his third year, since the age of horses was dated from May 1 at this time.

Following a series of victories by each of the quintet in spring preparatory races, Johnson and his head trainer Arthur Taylor traveled with the group from Virginia – primarily by water to avoid a grueling haul for the racers – to the Fairview Course in Bristol, Pennsylvania, placing the candidates approximately 90 miles from the Union. While continuing training at Bristol, Johnson’s first choice, John Richards, succumbed to injury; Washington was also taken out of training. The “Napoleon of the Turf’s” arsenal had been reduced to three runners, with John and Betsey Richards and Sir Henry remaining as possible competitors to face the Northern giant.

The Migration

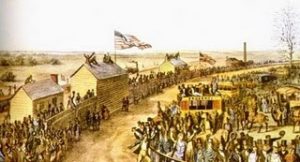

New York City had been teeming with tens of thousands of visitors, but on the afternoon of the Great Race on Tuesday, May 27, it was reduced to a noiseless metropolis — its masses having emptied out onto Long Island.

“The city has not been so deserted since the last visitation of the yellow fever,” the New York Statesman declared, referencing the previous summer’s epidemic that had stricken more than 400 people – killing nearly 250 – prompting an evacuation to Greenwich Village. “No carriages are to be seen or heard; the streets are as silent as midnight,” the Statesman continued about race day.

Earlier that Tuesday morning, the city had been a flurry of activity as fans set out on the nine-mile journey to Long Island by any means possible. John Pintard, the city’s first health inspector, wrote to his daughter about the scene at the ferry landing that a.m.:

Fulton to Pearl Street was blocked up with coaches, stages, double & single horse wagons, stages, Barouches & Gigs, 4 & 8 abreast all filled with Ladies & Dandies, high life & low life, waiting their turns for 2 Steam Boats and Horse Boats, incessantly plying across the Ferry, with row boats of all sorts & sizes, carrying over foot pads innumberable.

— Letter from John Pintard to Eliza Noel Pintard Davidson

Although he declined to attend the match himself, Pintard was no less zealous to learn of its result:

I am writing just before 2, & have sent Andrew to the Ferry for intelligence. I almost palpitate. What an old fool!

The youth Josiah Quincy Jr., who in later life would follow his father into public office as the Mayor of Boston, was determined to walk it to the track.

“Every conveyance in the city was engaged,” Quincy remarked. “Carriages of every description formed an unbroken line from the ferry to the ground. They were driven rapidly, and were in very close connection; so much so that when one of them suddenly stopped, the poles of at least a dozen carriages broke through the panels of those preceding them.”

Quincy’s party, however, was fortunate enough to procure an available carriage while en route to the track. “On arriving, we found an assembly which was simply overpowering; it was estimated that there were over one hundred thousand persons upon the ground.”

Although the projection for fans was more accurately estimated to be 60,000 – 20,000 of which were from the South alone – the disproportionate numbers overwhelmed the accommodations at the course. The stands and clubhouse, packed beyond capacity, hardly made an impact on the crowds, as nearly the entire one-mile circumference of the track was covered with carriages and spectators along the infield. Remarked New York’s National Advocate about the pandemonium at the course, “Booths erecting, Flags flying, Pigs roasting, Fiddlers tuning, and all dust & confusion.”

For the few New Yorkers left behind in the city, members of the Northern syndicate promised two methods for timely reporting of the race’s results. New York Evening Post Publisher Michael Burnham planned to print a second edition of the daily paper – the first sports extra ever published in American journalism. William Niblo, proprietor of the Bank Coffee House inn and restaurant, would dispatch from the Union “Niblo’s Express,” a rider commissioned to deliver to the newspaper an account of the race for writing the afternoon edition.

The results would also be announced by the hoisting of flags: at Niblo’s coffee house, a white flag to herald Eclipse’s victory, or a red flag in defeat; in Brooklyn at the Liberty Pole across from Young’s Hotel, a white flag to declare the supremacy of the North, or one with a pendant to indicate Eclipse’s loss.

Reports of the outcome “will be waited for with as much anxiety, as would the news of a battle or naval engagement,” the Statesman reported.

“Many an eye will be strained in looking for the flag to rise in the hazy atmosphere, and many a heart will palpitate when it is discovered.”

The Unveiling

Although the three finalists arrived at the Union a few days prior to the match, it was not until post time when Sir Henry was revealed to the world as the South’s challenger.

This choice wasn’t much of a surprise to anyone, due to Henry’s class, according to 20th century turf historian John Hervey; the colt had recently beaten Betsey Richards at Petersburg, Virginia, in his first test at four-mile heats, finishing in 7:54 and 7:58 – the fastest that track had ever seen. And as for Henry’s age, it served as an advantage with respect to weight. The four-year-old carried 108 lbs. in the match, versus Eclipse’s 126.

The two chestnut rivals, each with a star on their forehead and a white hind foot, and standing 15 hands high (Eclipse, 15 hands 3 inches; Sir Henry, 15 hands 1 inch), were brought up to the judges’ box. “The doubts which had been entertained (and there were many,) that the southern sportsmen would pay forfeit and there would be no race, vanished at once,” the Post reported, “and all was anxiety to see the result of the contest.”

The South was successful in delivering its most dynamic young competitor to face the mighty American Eclipse. Colonel Johnson, however, was nowhere to be found!

The defeat of Johnson proved to be the previous evening’s dinner celebration, a welcoming event hosted by the Northern syndicate, replete with libations and seafood delicacies. The Colonel, violently ill and utterly debilitated, remained bedridden at his hotel. For the race of all races, Johnson was absent.

“Thus the Southrons, deprived of their leader, whose skill and judgment, whether in the way of stable preparation, or generalship in the field, could be supplied by none other, had to face their opponents under circumstances thus far disadvantageous and discouraging,” reported Cadwallader Colden, otherwise known by his nom de plume, “An Old Turfman.”

Up Next: Part III. — See, the Conqu’ring Hero Comes!

If you missed Part I. of this series, read it here — Napoleon Challenges the North

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.